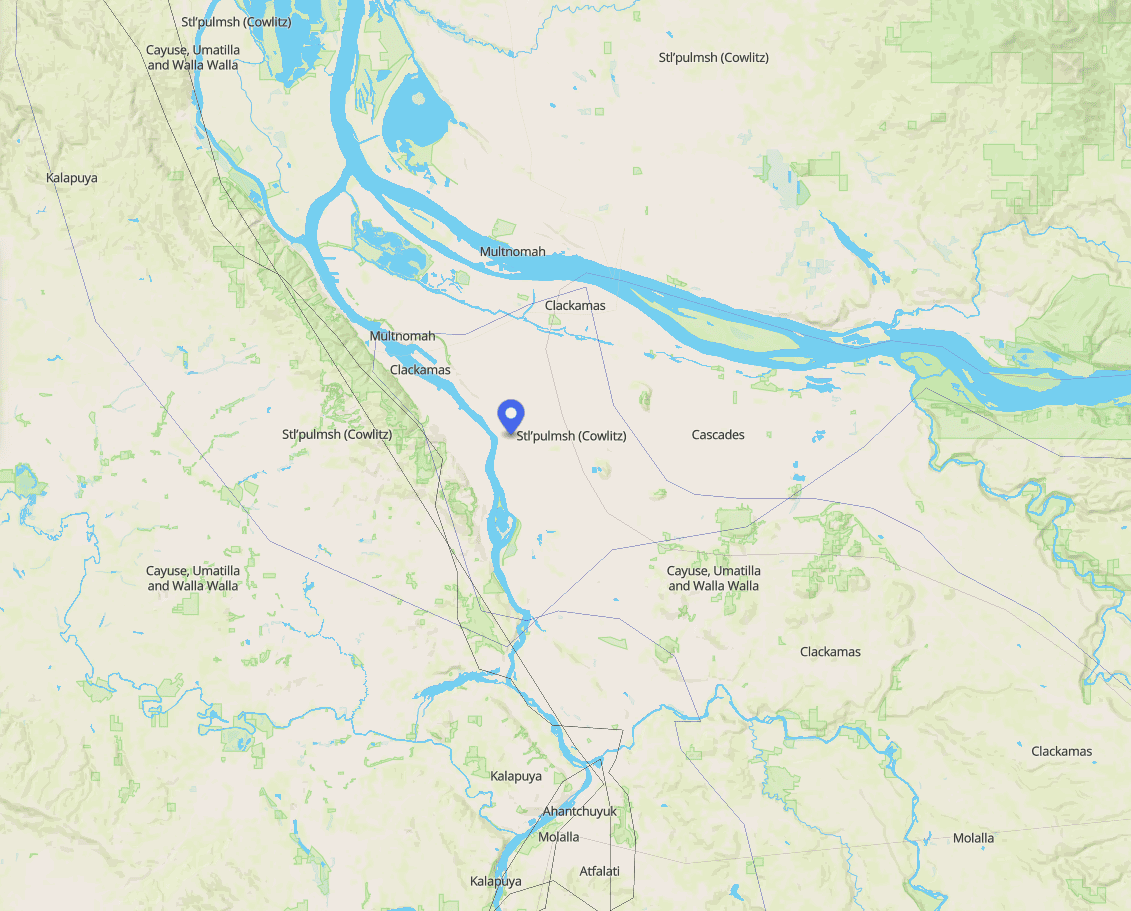

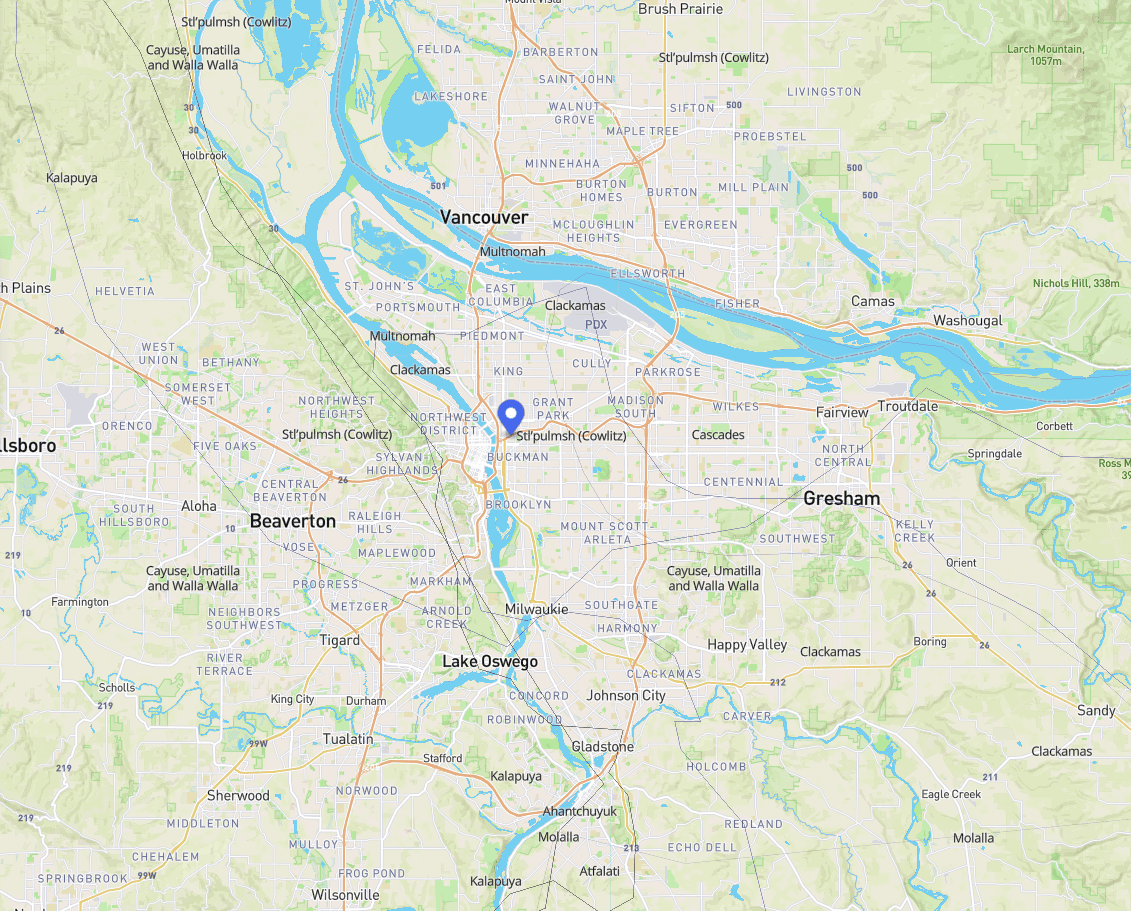

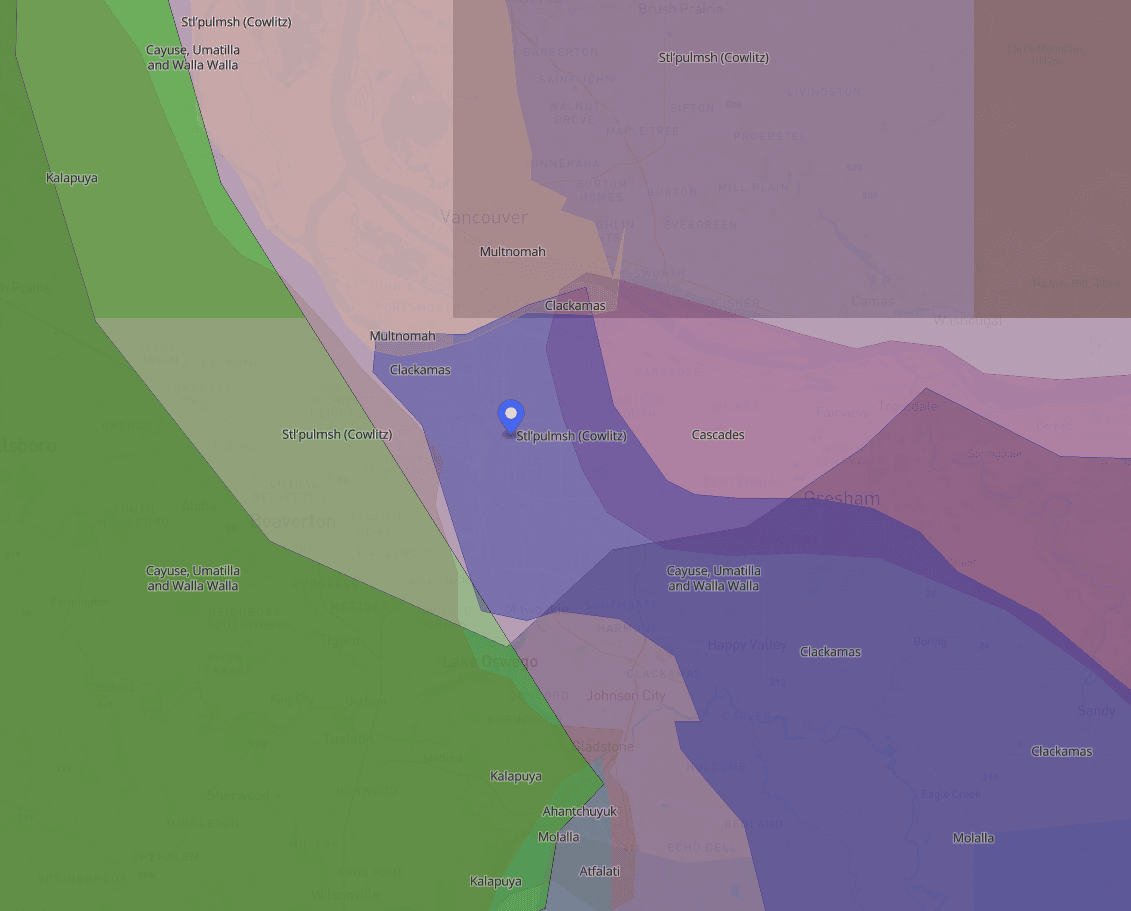

Indigenous Land Acknowledgement

Latest posts on the Gulch History Blog

Select Gulch History Articles

Below are select articles provided by Sullivan's Gulch historians:

The Long, Illustrious History of Sullivan’s Gulch

by John Scott

Timothy Sullivan, born in Ireland in 1805, seems to have traveled widely during his life. On January 8, 1841, while in Tasmania, he met the woman who would be his wife, Margaret.

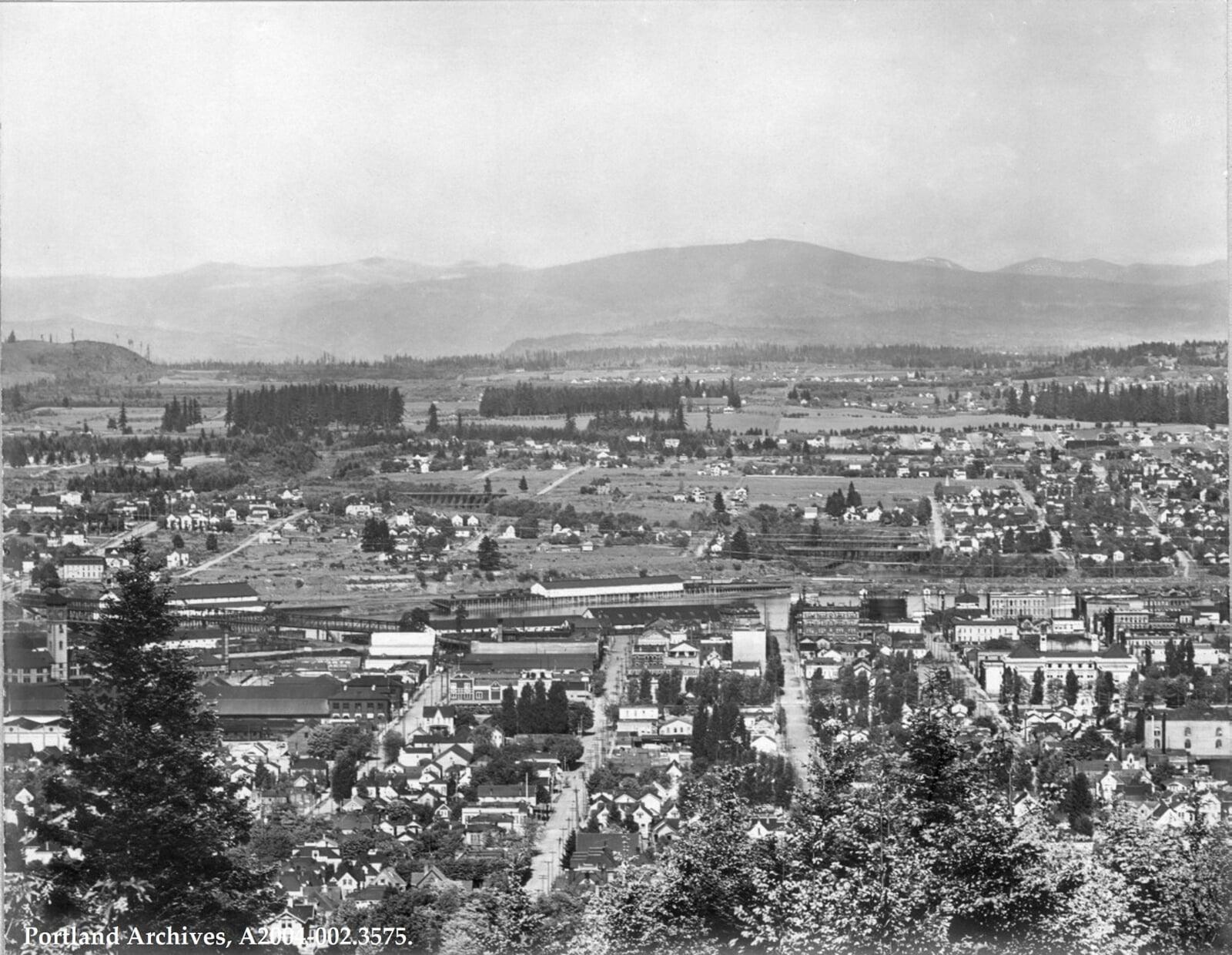

In January 1851, he arrived in East Portland and filed a Donation Land Claim for 320 acres. He was made a citizen of the United States on April 16, 1855 and received title to his claim at the same time. He built a cabin on the south edge of the gulch, which was in the northern part of his claim, near NE 19th Ave.

The gulch of 1851 is not the Gulch of today. To begin with, it is now called Sullivan’s Gulch. Back then is was mainly a forest of fir trees with a beautiful stream running through it and an occasional waterfall. Cougars and bears lived in the forest, too.

”Sullivan’s Spring“ was located near their cabin and became a popular site for picnickers. A mural depicting this bucolic scene appears on the outside back wall of the pub at 1700 NE Broadway. It was a project of Grace Academy, only one block away on NE 17th Avenue, that received a $5,000 grant from Confluence Project for public art projects in 2006.

Sullivan died in 1865. His wife moved to Vancouver, Washington, and died in 1890. Their daughter Marie inherited the property. She joined the Sisters of Providence Order and upon her death in 1904, she left the property to the Order.

The gulch often was prone to flooding, sometimes as far east as NE 16th. When the railroad came in 1881 the gulch was filled in to stop the flooding. As a result, land became available for an industrial zone and became the home for companies such as Doernbecker Furniture Factory and Hyster equipment manufacturing (located where Fred Meyer is today).

Many old-timers may have heard their parents or grandparents talk about Train #17, which headed into Portland in mid-afternoon everyday bringing cargo from the East. It passed right through their play areas in the gulch with its whistle blowing. You can still hear the whistles blowing in the night as trains pass through Portland.

As early as 1926 Portland's city planning commission began studying the feasibility of building a high-speed expressway through the gulch. The commission said, ”The plans as visualized contemplate an outgoing speedway on the right-hand side of the railroad tracks, an incoming lane on the left-hand side. The object would be to carry the speedway under all viaducts and to have only a few lateral streets, probably one every quarter or half mile to feed the through highway.“ The plans lay dormant until after World War II.

During the Great Depression in the early 30’s Shantytowns sprung up in the gulch, and it brought with it the first ”Hoovervilles.” The biggest settlement was near Grand Avenue with another one just east of NE 21st Ave. They eventually merged. They were self-contained “villages” governed by an elected mayor who forbade any liquor in the Shantytown. In 1933, there were 333 men living in 131 shanties in Shantytown.

The Dairy Cooperative Association provided daily deliveries of milk to the men. One of the mayor’s jobs was to make the rounds of nearby bakeries, grocery stores, and clothing stores to pickup donations. Portland Police Officer Howard, from Precinct #1, kept an eye on Shantytown and was helpful in making contacts for the mayor.

As the Depression began to end, the men in Shantytown began to drift away to find jobs that were beginning to open up in the logging mills. The population dropped to 100, and the final end to Shantytown came in 1941 when the shanties were deserted. A fire burned to the ground what was left.

After WWII ended, the plans for a freeway were revived in 1947 and won the approval of the state highway commission. The chairman of the commission was T. Harry Banfield. A campaign to have the name changed to ”Sullivan Gulch Pike“ failed.

A Brief History of Ben Holladay and Other Interesting Historical Persons, Dates, and Eventsand Other Interesting Historical Persons, Dates, and Events

by Emily Young (2017)

By the spring of 1864, Ben Holladay had acquired a dominant portion of the stage, mail, and freighting business between the Missouri River and Salt Lake City. He controlled 2,670 miles of stage lines and was among the largest individual employers in the United States. Holladay sold his routes to Wells Fargo Express in 1866 for $1.5 million and moved to Oregon. He became involved in a competition to build a railroad south along the Willamette River. In 1868 ground was broken for routes along both the east and the west sides of the river. Holladay’s “Eastsiders” completed 20 miles of track before the competition, which subsequently sold out to him. Holladay won a federal subsidy and built the Oregon and California Railroad as far south as Roseburg before the Panic of 1873 financial crisis stopped the effort. In 1876 Henry Villard took over the railroad. At his peak, Holladay entertained lavishly and spent a great deal of money in an unsuccessful bid for a seat in the U.S. Senate. In contrast to his youth growing up in a log cabin, by the age of 50 Holladay maintained mansions in Washington D.C., on the Hudson River in New York, and in Portland. He also kept an elaborate “cottage” at Seaside, Oregon.

There are two wonderful books on Ben Holladay:

- Ben Holladay, the Stagecoach King: A Chapter in the Development of Transcontinental Transportation, 1940 & 1968 by

J. V. Frederick - The Saga of Ben Holladay: Giant of the Old West, 1959 by Ellis Lucia

Holladay must have had lots of influence since we have many significant properties named after him.

Legacy Holladay Park Medical Center (Emanuel), Holladay Park Post Office, Holladay Park Plaza, Holladay Park Church of God, and NE Holladay Street. Also, Sullivan’s Gulch tax properties are identified as Holladay Park Addition by the county and state.

Other interesting historical persons, dates, and events for Sullivan’s Gulch:

- It is said Ben Holladay planted the first trees for Holliday Park in the 1880s. He also built two large hotels in the area where the park bearing his name is now located.

- The oldest house is a surviving Victorian cottage on NE Weidler, built in 1886.

- Holladay Park was commissioned by the Lloyd Corporation and Pacific Power & Light in 1964, and a concrete fountain featuring music and lights was installed in the park. Designed by Jack Stuhl, assisted by Ted Widing and Phillips Electrical, the musical fountain was a favorite gathering place for park visitors. It was replaced in 2000, in conjunction with a major renovation of the park, by a spouting fountain designed by Tim Clemen and Murase Associates. Holladay Park was made the official park of Sullivan’s Gulch in 2000. Pat Svenson was an important SG neighbor who made this happen. I knew Pat for many years and she was instrumental in helping with many issues in Sullivan’s Gulch. Her obituary is online, but it does not mention her neighborhood activities. (neighborhood activism does not appear often in obits)

- Three cast-bronze sculptures by artist Tad Savinar were added to the park as a percent-for-art project in 2000. Entitled Constellation, the project illustrates the connection between the personal front yard garden and the civic park garden through three distinct elements: a vase of cut flowers, an abstract molecule containing elements of a good neighborhood, and the figure of a home gardener, shears in hand. The objects in the molecule were selected by the Sullivan’s Gulch Neighborhood Association and the gardener was modeled after Carolyn Marks, a longtime Sullivan’s Gulch neighborhood activist.

- First home demolitions in Sullivan’s Gulch and surrounding areas happened in the mid 1950s and 1960s and resulted in the many apartments we still see today.

- Lloyd Center opens in 1960.

- The Fontaine was built in 1963.

- Holladay Park Plaza first phase construction in 1968.

- SGNA Articles of Incorporation were filed with the city and state in 1980 to make Sullivan’s Gulch an official neighborhood with its own neighborhood association. Find it on the SGNA website under the Board menu about SGNA.

- Fred Meyer moved from the Hollywood District to Sullivan’s Gulch in the early 1990’s. The Fred Meyer store replaced the Hyster plant that was on the current property. Sullivan’s Gulch Neighborhood Association was very active and helped make the move more friendly by aggressively getting streets blocked at 28th so that racing through the neighborhood could not happen.

The History of Sullivan’s Gulch

- Abbott, Carl. The Great Extravaganza. Portland OR: Oregon Historical Society, 1981tt, Carl. The Great Extravaganza. Portland OR: Oregon Historical Society, 1981tt, Carl. The Great Extravaganza. Portland OR: Oregon Historical Society, 1981tt, Carl. The Great Extravaganza. Portland OR: Oregon Historical Society, 1981

- City Club of Portland. “Sullivan’s Gulch Highway Project” 1946

- Frazier, Bob. Column. Sunday Journal Magazine 27 January 1952

- “Lloyd Center sprang from 100 years of dreams” Oregonian 27 July 1975

- Snyder, Eugene. We Claimed This Land: Portland Pioneer Settlers. Portland OR: Binford & Mort Publishing, 1989.

- Staehli, Alfred. Preservation Options For Portland Neighborhoods. Portland OR: Alfred Staehli AIA, 1975

- “How Gulch Got Name” Column. Oregon Journal 26 February 1950

- “Mayor of Shantytown Happy as Men Pack Up and Leave for ‘somewhere’” Oregonian 11 May 1933

- “Old Sullivan’s Gulch Is Gone — But Memories Linger On” Column. Oregon Journal 24 November 1957

- “On one city block, Portland’s past and future meet” Oregonian 23 August 1999

- “Our Banfield Cost $1,000,000 a Mile” Oregon Journal 24 November 1957

- “Shantytown Takes Stride Ahead Under Guiding Hand of New Mayor” Oregonian 27 February 1933

- Sullivan’s Gulch Neighborhood Association. “History” Swenson, Dr. Patricia L. 30 March 1999, http://WWW.sulivansgulch.orgy” Swenson, Dr. Patricia L. 30 March 1999, http://WWW.sulivansgulch.orgy” Swenson, Dr. Patricia L. 30 March 1999, http://WWW.sulivansgulch.orgy” Swenson, Dr. Patricia L. 30 March 1999, http://WWW.sulivansgulch.org

Have neighborhood history or stories to share?

Other Local History Resources

Although we are not affiliated with the following resources, they have provided a plethra of interesting photos, articles, and content of local Portland history.

Vintage Portland

Vintage Portland is a community project that was given to the Portland City Archives to administer in 2013. This blog allows the City Archives to showcase materials from the collection and gives community members the opportunity to engage with them.

Alameda Old House History

Doug Drecker started alamedahistory.org in 2007 as a blog dedicated to collecting and sharing research about old houses, buildings and neighborhoods in northeast Portland, Oregon.

Portland City Archives

The Archives & Records Management Division of the Portland City Auditor’s Office is the official home of the City’s historic records.

The online eFiles catalog contains many photos and other resources.